The Trigger That Closed the U.S. Gold Window

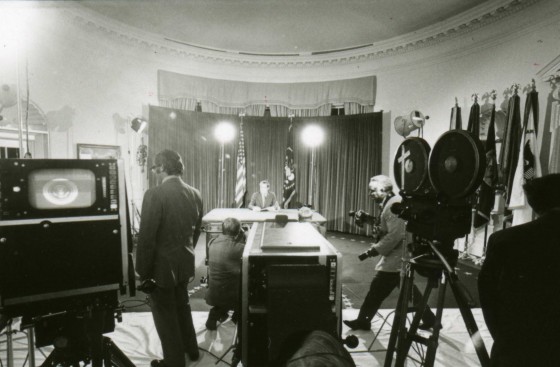

“I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, except in amounts and conditions determined to be in the interest of monetary stability and in the best interests of the United States."

– Richard Nixon, Sunday 15 August 1971

Exactly 50 years has passed since the US Government famously suspended the convertibility of US dollars into gold on 15 August 1971 in a speech announced by then US president Richard Nixon.

This convertibility of US dollars into gold applied to US dollars held by foreign governments and foreign central banks, which based on the rules of the Bretton Woods monetary system, allowed them to legally show up anytime at the ‘gold window’ of the US Treasury and exchange their excess US dollars for physical US Treasury gold.

There will be much written this month about the 50th anniversary of the closure of the US gold window, but less so about what exactly triggered it and why the timing had to be 15 August.

So without further ado, here is why, and it all revolves around the British ambassador to the US. the 3rd Earl of Cromer, a.k.a. George Rowland Baring, showing up at the US Treasury offices in Washington D.C. on 12 August 1971 and demanding that US dollars held by Britain be converted into gold.

A Weakening Dollar – The System under Strain

Early 1971 saw a noticeably growing US balance of payments deficit, with governments and central in major economies accumulating ever larger quantities of US dollars in volumes far exceeding the US Government’s (US Treasury’s) stock of gold. The US trade balance also moved into deficit.

In April 1971, major currencies began to appreciate against the US dollar in the forward markets, and currency volatility increased as central banks outside the US (chiefly in Europe) tried to stabilize their currencies against the US dollar by taking in large amounts of dollars and selling their domestic currencies (after expanding their own money supplies), which at the same time added to inflationary pressures in their economies.

This volatility caused Eurodollar interest rates to rise, which attracted further speculative dollar inflows into European countries led by West Germany, and triggered wider European currency trading bands as these currencies strengthened against the US dollar. On 10 May 1971 the Bundesbank was forced to float the Deutschemark, and the US dollar began falling in value against the West German currency.

This in turn led to the belief that the US dollar would be formally devalued, which in turn caused further speculative inflows into other currencies and out of the US dollar, and led to central banks in Europe holding huge amounts of unwanted US dollars.

On Friday 6 August 1971, Henry Reuss, Chairman of the Joint Economic Committee on Exchange and Payments, said that the US dollar was overvalued and the next day his Committee released a report reiterating this statement. This in turn caused further turmoil on the financial markets when they reopened on Monday 9 August 1971.

Panic about a Gold ‘Drain’

Given the limited amount of gold that the US Treasury held, or claimed to hold, versus the far larger amount of US dollars in the hands of ‘foreign’ central banks all over the world, this naturally caused panic in the US government and the US Treasury that the remaining US gold stockpile would be ‘drained’ by foreign central banks converting their huge US dollar balances into gold at the US Treasury gold window.

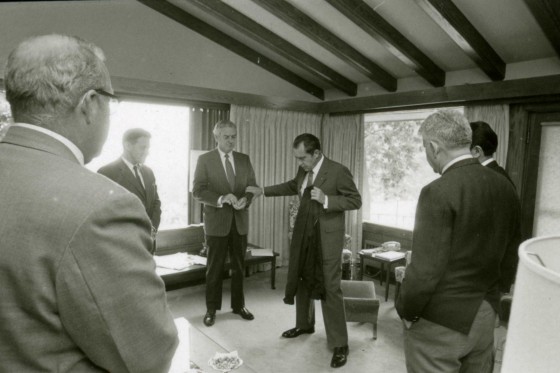

The panic to prevent a gold drain was clear even from early August 1971 and can be seen in a 2 August 1971 discussion between US president Richard Nixon, US Treasury Secretary John Connally, US Director of the Office of Management and Budget George Schultz, and White House Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, which appears in the famous Nixon tapes.

This 2 August 1971 discussion is fascinatingly explained in a 2009 University of Delaware thesis submission paper by Scott W. Ohlmacher titled “The Dissolution of the Bretton Woods System, Evidence from the Nixon Tapes, August – December 1971”

Ohlmacher writes:

“Connally continues to stress just how important it is to stop the gold drain.”

Connally [direct quote]: ‘In the international field the problem is one – the convertibility of dollars into gold and we’re going to have to stop that at some point…Everybody, I say ‘everybody’, most people tend to think that ten billion dollars [in gold reserves] is the point below which we should not go.’

Much later in the conversation, Nixon and Connally are joined by Haldeman. Connally and Haldeman detail just how serious the gold drain has become. Haldeman notes that the United States has lost $850 million in gold reserves in the week of August 2, 1971 alone.”

Connally continues that the French have called in over $1 billion in reserves in the past few weeks and that the Germans and the Dutch are looking to call in some $200-250 million more. Connally thinks that the President could hold on a decision until mid-September, but not later.”

[Source: Tape – August 2, 1971 (Conversation Number 553-6) Nixon with Connally and Shultz. White House Chief of Staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman enters later. “The Dissolution of the Bretton Woods System, Evidence from the Nixon Tapes, August – December 1971” By Scott W. Ohlmacher, 2009. Thesis submission, University of Delaware]

France Spooks the Yanks

The list of countries demanding US gold during July 1971 included Switzerland, which bought $50 million in US Treasury gold, and France, which converted $191 million into gold. These gold transactions are confirmed by a 21 July 1971 US Federal Reserve Board of Governors report which states that:

“In official transactions this month…the U.S. Treasury sold $50 million equivalent of gold to Switzerland.”

“In August the U.K. and France will be repaying $638 million and $600 million equivalent, respectively, to the IMF. France has already notified the U.S. Treasury of its intention to purchase the $191 million in gold required for its [IMF] Fund repayment.”

(Source – Fed Greenbook 21 July 1971)

This $191 million gold sale to France did definitely go through in early August as the August 1971 Fed Greenbook states that:

“Late in the afternoon of Friday, August 6, the U.S. announced its Fund drawing of $862 million equivalent in Belgian francs and Dutch guilders plus the sale of $191 million in gold to France.”

Source – Fed Greenbook 18 August 1971)

A sum of US $191 million at $35 per troy ounce would mean France purchased 5.457 million ozs of gold (169.74 tonnes). This could have been the same gold which the French are said to have then transported back to France by military ship from the east coast of the United States (see below). As the Banque de France is an IMF gold depository, it would still be logical to bring the gold back to Paris since the gold purchase was intended to pay back the IMF and could be transferred into the IMF gold holdings at the Banque de France.

In addition to this $191 million gold purchase by France, it appears that in early August 1971, the French wanted to buy even more US Treasury gold and maybe did so. The French had also, according to US Treasury Secretary Connally (see above) “called in over $1 billion in reserves in the past few weeks.“

But beyond this, the British request for US Treasury gold was the main event of August 1971. There is ample evidence in everything from archives to academic papers to the memoirs of the US Government officials involved, that it was French but crucially British requests to exchange US dollars for gold in the week prior to 15 August that forced the US government to close the gold window and suspend US dollar convertibility into physical gold.

A quick review of some of these sources adds color to proceedings. Note that the French president at the time in 1971 was Georges Pompidou. The British prime minister at the time in 1971 was Edward Heath. The US president at the time in 1971 was Richard Nixon.

Hello Chaps, We’d like $3 Billion in Gold

In a 2016 article by Chris Barber titled “The Burden of Bretton Woods” published by the Nixon Foundation, Barber writes that:

“In the second week of August 1971, the British ambassador appeared before the United States Treasury and asked that $3 billion be converted into gold to act as “cover” for all their dollar assets.

It was then, in the midst of impending economic calamity, that Nixon had to confront the major crisis.”

In 2017, a NBER working paper by Michael D. Bordo, tells us that:

“The decision to suspend gold convertibility by President Richard Nixon on August 15 1971 was triggered by French and British intentions in early August to convert dollars into gold.”

[Source: “The Operation and Demise of the Bretton Woods System; 1958 to 1971” Michael D. Bordo, Working Paper 23189, National Bureau Of Economic Research (NBER)]

In 2011, the well-known Yanis Varoufakis (who would go on to be Greek Minister of Finance in 2015) in an article about currency unions and recycling dollar surpluses tells us that:

“In August of 1971 the French government decided to make a very public statement of its annoyance at the United States’ policies: President George Pompidou ordered a destroyer to sail to New Jersey to redeem US dollars for gold held at Fort Knox, as was his right under Bretton Woods!

A few days later, the British government of Edward Heath issued a similar request, though without employing the Royal Navy, demanding gold equivalent to $3 billion held by the Bank of England. Poor, luckless Pompidou and Heath: They had rushed in where angels fear to tread!”

A 2016 paper by Michael J Graetz of Columbia Law School, titled “A ‘Barbarous Relic’: The French, Gold, and the Demise of Bretton Woods”, also covers the French and British maneuvers saying that:

“In August 1971, French president Pompidou sent a battleship to New York harbor to remove France’s gold from the vault of the New York Federal Reserve Bank and to transport it to the Banque de France in Paris. Soon thereafter, gold accounted for 92 percent of French reserves.

On August 11, the British requested that the Treasury remove the $3 billion of gold from the U.S. depository of Fort Knox to the New York Federal Reserve vault, where the gold of foreign governments was stored.”

The British request to the US Treasury is reiterated in the monetary history book titled “The Commanding Heights: The Battle for the World Economy” by Daniel Yergin and Joseph Stanislaw (1997) in which they write:

“In the second week of August 1971, the British ambassador turned up at the Treasury Department to request that $3 billion be converted into gold.”

Further evidence comes from a 1993 book by Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten titled “Changing Fortunes: The World’s Money and the Threat to American Leadership”. Paul Volcker was at that time in 1971 the US Treasury Undersecretary for Monetary Affairs, and states that:

“On Thursday, August 12, the Bank of England requests unspecified devaluation cover for its dollar reserves of about $ 3 billion. The Federal Reserve draws $2.2 billion on its swap lines, including $750 million for the Bank of England.”

Volcker, who was at the heart of the matter, then makes clear that this unspecified devaluation cover that the British requested was in the form of gold:

“If the British, who had founded the system with us, and who had fought so hard to defend their own currency, were going to take gold for their dollars, it was clear the game was indeed over.”

This massive sum of $3 billion in gold would have been equivalent to 2,666 tonnes of gold, and the US Treasury at that time claimed to hold less than 10,000 tonnes of gold. That would be over 25% of all claimed US Treasury gold.

While the Americans did not want to agree to one foreign central bank request for US dollar conversion into gold for fear of setting off a stampede of other central bank gold requests, it’s also possible that the US Treasury did not have all the gold at claimed to have in Fort Knox or at the New York Fed vault in Manhattan (at least not in Good Delivery gold bars), and that the Americans balked at a demand for 2,666 tonnes simply because they did not have enough gold to sell.

The Bank of England knew back in March 1968 when the London Gold Pool collapsed that the Americans had run out of Good Delivery gold, as is clear from a Bank of England memo from 14 March 1968 which said:

“It has emerged in conversations with the Federal Reserve Bank that the majority of the gold held at Fort Knox is in the form of coin bars, and that in certain cases these bars have a gold content of less than 350 fine ounces. If the drain on U.S. stocks continues it is inevitable that the Federal Reserve Bank will be forced to deliver what bars they have."

“It would appear that the circumstances might well be such that very few bars of the current acceptable fineness could be found“

[Bank of England file C43/323/49]

[See BullionStar article “The Keys to the Gold Vaults at the New York Fed – Part 3: ‘Coin Bars’, ‘Melts’ and the Bundesbank” for details of this March 1968 Bank of England memo.]

So the Bank of England, more than any central bank in the world, would know the real truth about US Treasury gold holdings, as the scramble for US Treasury gold accelerated in August 1971.

Across some sources, there is controversy about whether the British demanded US$ 3 billion in gold or US$ 750 million in gold in the days before 13 August 1971.

The Earl of Cromer – Blue Blooded Baring

This is where the British ambassador to the USA at that time, George Rowland Stanley Baring, a.k.a. The 3rd Earl of Cromer, enters the picture. Baring, known as Rowland Baring, was not your ordinary diplomat, as he was also one of the highest level bankers of his time, and hailed from the famous Baring bankers family.

In fact, Rowland Baring ran Baring Brothers bank between 1949 and 1959. Other strings in Rowland Baring’s bow included being Governor of the Bank of England between 1961 and 1966, being a previous economic minister of the British embassy in Washington, being previous head of the United Kingdom Treasury and Supply Delegation, being an Executive Director of the World Bank in Washington, and being a Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army (like my grandfather).

#royal #flashback “Prince Edward, Duke of Kent with Katharine, Duchess of Kent meet British Ambassador to the USA Rowland Baring, 3rd Earl of Cromer and his wife Esme in the grounds of the British Embassy during a visit to Washington DC, United States on 12th October 1972 pic.twitter.com/NwqpBS5xnj

— Mace (@RoyaleVision) October 12, 2019

The Earl of Cromer was thus very familiar with both the Bank of England and the HM Treasury (British Treasury), as well as the way politics and economics worked in Washington DC. Baring had additionally also previously worked at JP Morgan & Company, Morgan Stanley & Company, and Kidder, Peabody & Company so was totally immersed in and connected to the New York – London axis of the ‘old wealth’ banking elite. In fact, he was the ‘old wealth’ banking elite.

So when The Earl of Cromer (who lived in the British Embassy in Washington DC between 1971 and 1974) strolls into the US Treasury offices in DC and says “Hello chaps, we’d like US$ 3 billion in gold on behalf of Her Majesty”, the yanks are going to sit up and take notice.

And that is exactly what happened. On 12 August 1971, The Earl of Cromer (Rowland Baring) turned up in the US Treasury in Washington DC on behalf of the Brits (HM Treasury and Bank of England), requesting that the US Treasury convert US $3 billion held by Britain into gold. This figure was then seemingly negotiated down to US$ 750 million, because the Americans were shell shocked.

In his 1976 book, “The Arena of International Finance”, Charles Coombs refers to the Cromer visit on page 217-218, quoting Treasury Secretary John Connally (page 218). Connally said:

“What’s our immediate problem? We are meeting here today because we are in trouble overseas. The British came in today to ask us to cover $3 billion, all their dollar reserves. Anyone can topple us – anytime they want – we have left ourselves completely exposed."

Why was it a problem? Why could anyone topple the monetary system of the United States at any time? Perhaps it was because the Americans did not have as much gold as they claimed to have.

Coombs then comments that:

“Connally’s citation of the eleventh-hour British request for $3 billion of exchange cover as an example of imminent foreign attacks on the dollar is a travesty on the facts.

The Bank of England request for cover, quickly agreed in the amount of $750 million rather than $3 billion, was a direct consequence of justifiable British suspicion that the Treasury was on the verge of closing the gold window.“

Charles Coombs isn’t just any author as he had a 30-year career at the New York Fed, where he rose to be Head of Foreign Exchange Operations of the New York Fed, and he also for 16 years, was manager of the Open Market Committee for the overall Federal Reserve System.

What’s $3 Billion or $750 Million between friends

Coombs’ comment implies that what started as a request for US$ 3 billion by the Earl of Cromer was ‘quickly agreed’ at $750 million, which at $35 per troy oz would be 666.5 tonnes of gold. Still a huge amount of gold.

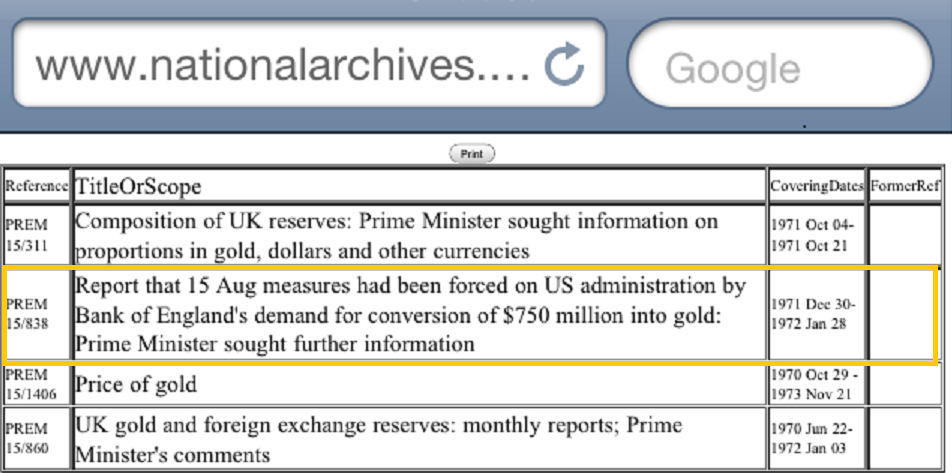

There is substance to the Coombs version of events, since there is a HM Treasury file in the National Archives in Kew, London (which I have visited and have read) titled “Report that 15 Aug measures had been forced on US administration by Bank of England’s demand for conversion of $750 million into gold: Prime Minister sought further information“. (File ref PREM 15/838 can be seen on the National Archives catalogue website here).

This file confirms that British ambassador, Rowland Baring (The Earl of Cromer) turned up at the US Treasury offices in Washington DC, and refers to the US$ 750 million request to be converted into gold.

In the book, “Richard Nixon and Europe” by American historian Luke Nicther, published in 2015, Nicther refers again to the US$ 3 billion figure:

“Great Britain planned to submit a massive request to convert US $3 billion into gold [footnote 93].

The request was received by Charles Coombs of the Federal Bank of New York on August 13, while visiting the Treasury Department in Washington [footnote 94].

The British request caused panic in the [US] Treasury and prompted Connally’s early return to Washington. The request indicated that the British government presciently understood that the time for remaining gold conversions was short. The United States was forced to act.

Should the British request be granted, the publicity of such a large transfer of gold would cause a European run on the Federal Reserve at the worst possible moment. …With less than 10 billion in gold reserves, before the British request, an American default loomed.”

Footnote 93 of Nicther’s book states that there are multiple memoirs of the people involved which mention the British request, including the memoirs of Connally, Haldeman, Stein, and William Safire.

The UK National Archives PREM 15/838 file also contains a letter from 13 August 1971 from the British Treasury (HMT) to the British Prime Minister’s office (Edward Heath’s office), denying that the gold conversion request had ever been made, saying that:

“at no time did the Bank of England ask for conversion of US dollars into gold/ nor is there any basis for a figure of $3 billion.”

[This 13 August 1971 letter is from Alan Bailer, Office of the Chancellor of the Exchequer (HM Treasury) to Robert Armstrong, 10 Downing Street (Prime Minster’s Office)]

As you can see from the carefully crafted wording of Bailey’s letter, this denial by HM Treasury did not say that HM Treasury didn’t ask for conversion of US$ 3 billion into gold on behalf of Britain’s Exchange Stabilisation Fund (EEA), nor that the British Government didn’t ask for conversion of US$ 3 billion into gold, merely that the Bank of England did not request conversion of US$ 3 billion. On a technical point, the Bank of England does not own any of Britain’s gold, it merely stores it. It’s the Exchange Stabilisation Fund, administered by HM Treasury, which owns British reserve assets, including US dollars and gold.

Also, given the fact that the dollars for gold request did take place (since there is a huge amount of evidence above to prove it), this HM Treasury denial can be taken as par for the course for weasel words governments, which, as we all know, lie all the time, even inter-departmentally to each other.

Bank of England Memos – Top Secret

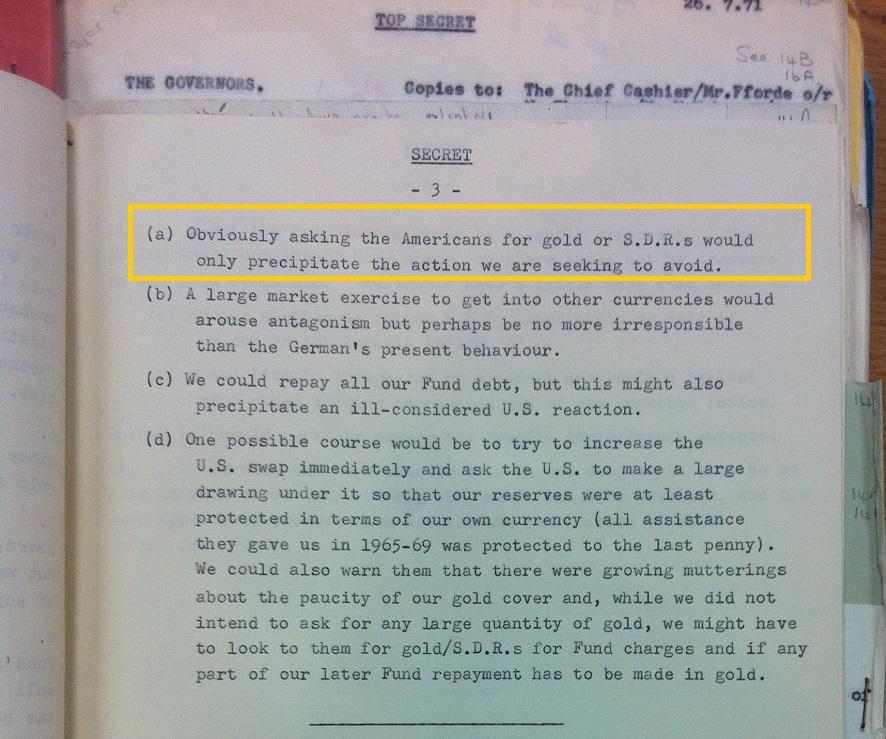

If we turn to the Bank of England archives, there is also ample evidence in Bank of England file OV53/60 – International Monetary Reform 1971 that the Bank of England was for weeks before 15 August 1971 actively discussing the issue of the Americans closing the gold window and preparing for that outcome.

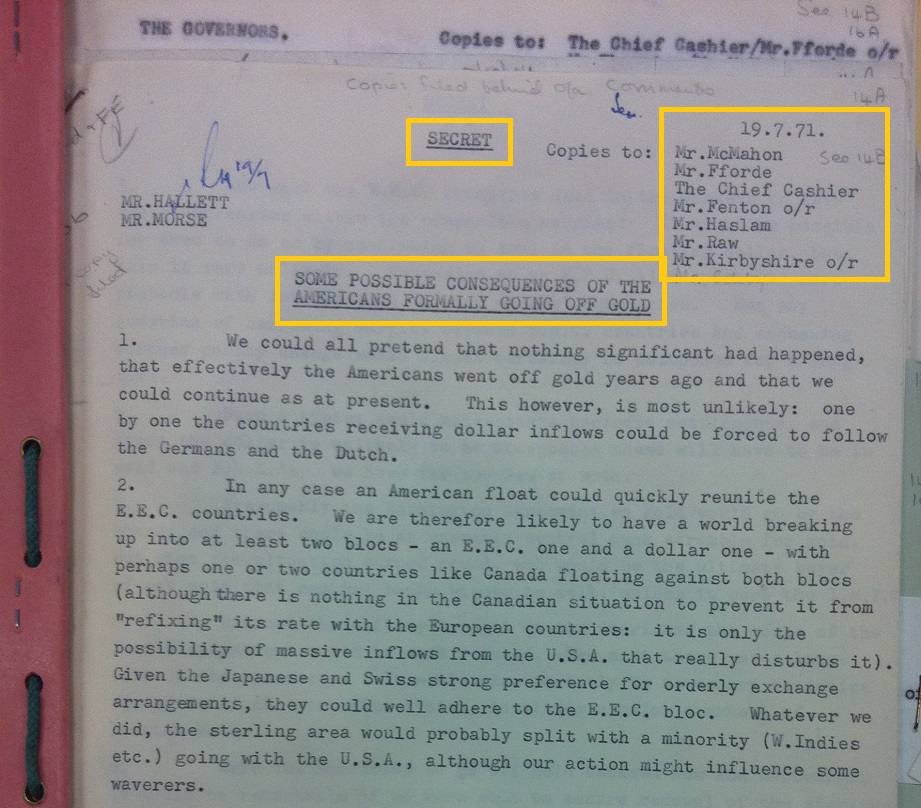

First up is a Bank of England internal paper from 19 July 1971, marked ‘Secret’, and titled “Some Possible Consequences of the Americans Formally Going Off Gold‘. This paper, which was written by Bank of England expert John Sangster (JLS) and circulated among senior executives of the Bank, discussed the scenario of the US closing the gold window and the alternatives the British had to chose from if that outcome occurred. See screenshot below.

Point 11 of that Secret paper from 19 July discussed what to do about converting US dollars into US Treasury gold:

“11. The more immediate question is how do we protect the $4.1 bn of reserves held in US dollars. Admittedly we have long term debts in US dollars of $5.5 bn but substantial losses on our short-term assets would weaken our intervention ability…:

See screenshot below:

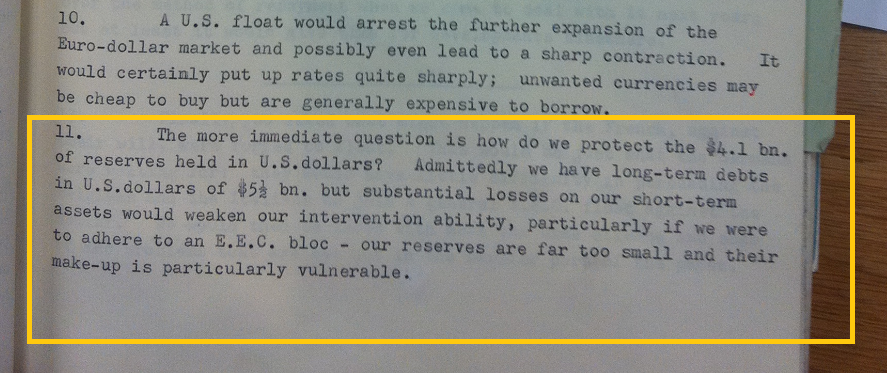

There then followed a list of options about how the British would protect their $ 4.1 billion of reserves held in US dollars. Option (a) was:

“Obviously asking the Americans for gold or SDRs would only precipitate the action we are seeking to avoid“.

See screenshot below:

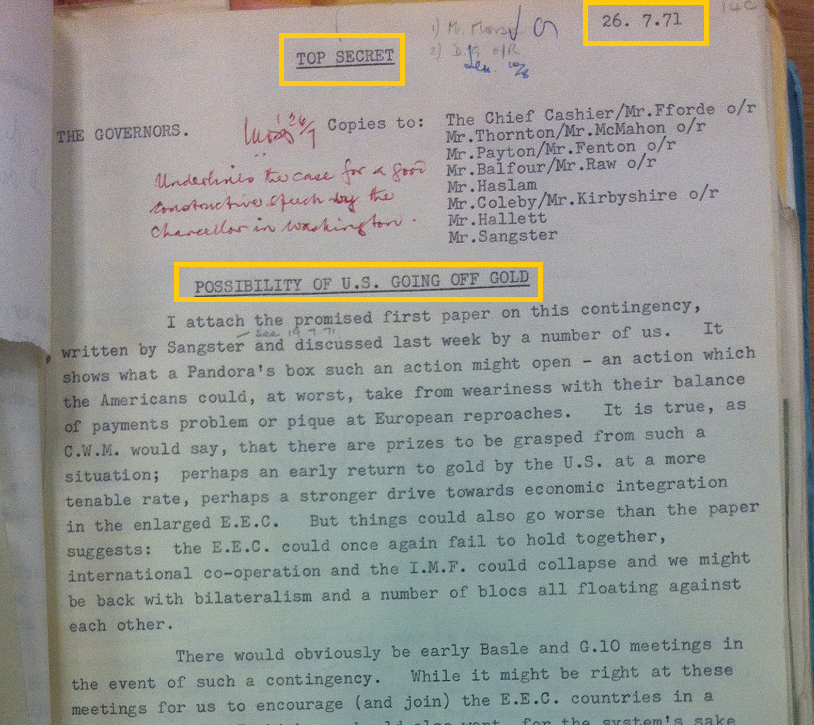

On 26 July 1971, this paper by Sangster was circulated more widely among top Bank of England executives, in a ‘Top Secret" memo titled “Possibility of US Going Off Gold" which began with the recognition that closing the gold window might open a Pandora’s box of both opportunities and threats. See screenshot below:

“Demand a Massive Amount of Gold from the Americans"

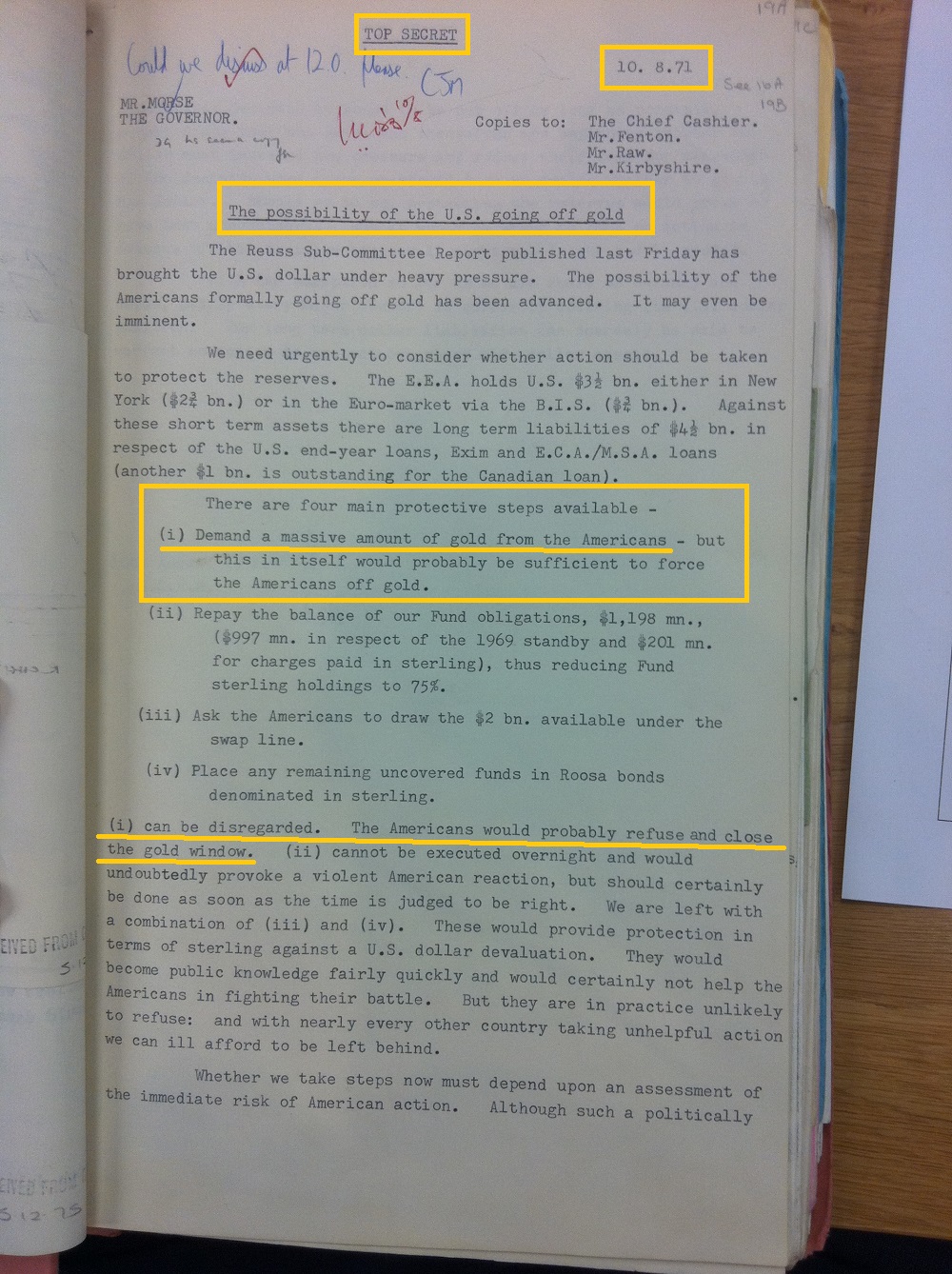

On Tuesday 10 August 1971, the Bank of England circulated another internal Top Secret memo, with a similar title “The Possibility of the US Going Off Gold“. This time the Bank listed the options available to protect the British reserves from the eroding value of the US dollar, including the first option ‘Demand a massive amount of gold from the Americans’ They actually used these exact words:

“The Reus Sub-Committee Report published last Friday has brought the US dollar under heavy pressure. The possibility of the Americans formally going off gold has been advanced. It may even be imminent.

We need urgently to consider whether action should be taken to protect the reserves. The EEA [Exchange Equalisation account] holds US $3.5 bn, either in New York ($2.75 bn) or in the Euro-market via the BIS ($0.75 bn).

Against these short term assets are long term liabilities of $4.5 bn in respect of the US end-year loans, Exim and ECA/MSA loans (another $1 bn is outstanding for the Canadian loan).

There are four main protective steps available –

(i) Demand a massive amount of gold from the Americans – but this in itself would probably be sufficient to force the Americans off gold."

The memo then listed options (ii) pay IMF obligations so as to reduce dollar balances, (iii) ask the US to draw $ 2 billion on the inter-central bank swap lines, and (iv) put any remaining funds into Rossa bonds denominated in sterling.

The memo said that option “(i) can be disregarded. The Americans would probably refuse and close the gold window“.

Option (ii) could not be done quickly, said the memo. That left options (iii) and (iv) which would protect sterling in the event of a dollar devaluation.

See screenshot below of Page 1 of this memo:

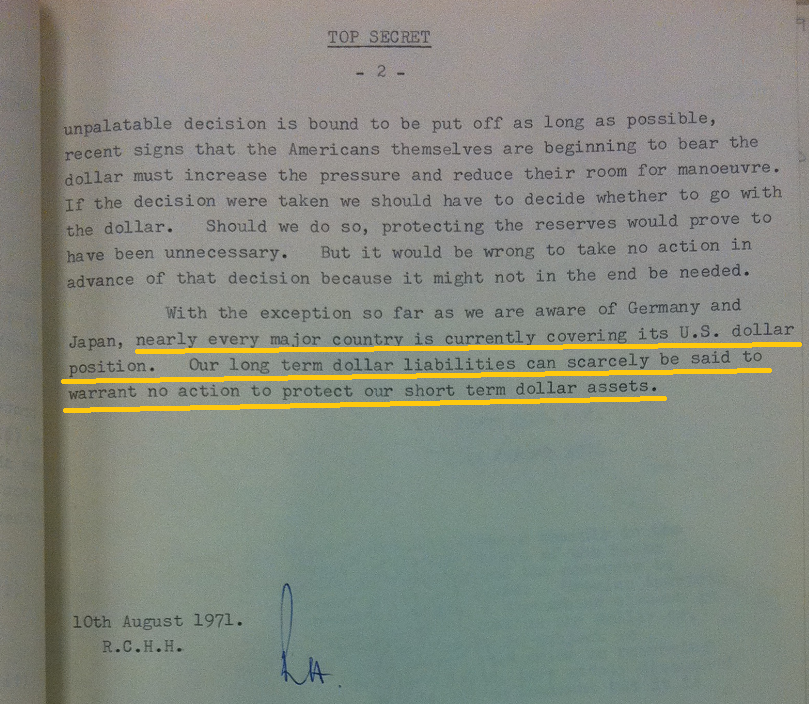

However, the memo then said, in a typically convoluted and rambling way used by the old Bank of England chaps, that even though the Americans might try to protect the value of the dollar, and the British help out on that front, that it was also wise in the meantime to protect the reserves of the Exchange Equalisation Account by covering it’s US dollars assets.

See screenshot below of Page 2 of this memo:

Covering their Assets

And what did the old chaps in the Bank of England mean by ‘covering their US dollar assets‘? Why of course, it meant asking the Americans to convert Britain’s dollar balances into gold bars.

Which is preciously why the Earl of Cromer, Rowland Baring, strolled into the US Treasury offices 2 days later and asked that US$ 3 billion of Britain’s US dollar holdings be converted into gold bars.

Recall the use of the word COVER in various quotes above:

Barber (2016) – “In the second week of August 1971, the British ambassador appeared before the United States Treasury and asked that $3 billion be converted into gold to act as “COVER” for all their dollar assets."

Volcker and Gyohten (1993) – “On Thursday, August 12, the Bank of England requests unspecified devaluation COVER for its dollar reserves of about $ 3 billion. The Federal Reserve draws $2.2 billion on its swap lines, including $750 million for the Bank of England.

..If the British… were going to take gold for their dollars, it was clear the game was indeed over.”

Coombs (1976) – quoting Connally “The British came in today to ask us to COVER $3 billion, all their dollar reserves

Coombs again – “The Bank of England request for COVER, quickly agreed in the amount of $750 million rather than $3 billion, was a direct consequence of justifiable British suspicion that the Treasury was on the verge of closing the gold window.“

And that is how the British bankers via the Earl of Cromer triggered the US to close the gold window at that precise time on 15 August 1971, knowing that “The Americans would probably refuse and close the gold window“.

Which is what the Americans then did. This gold window closure then ushered in the US dollar fiat era, a 50 year period of a fake and eroding world reserve asset, the fallout of which we see right up to this day, and which has been responsible for totally altering the world’s monetary and economic landscape, and not in a good way. (See the fantastic visual charts website https://wtfhappenedin1971.com for details of why this is so.)

An important question arising from Cromer’s request to the US Treasury is who was working for who, and who benefited from the gold window closure.

Was it the outcome of a random set of events? Or was there a joint US-British decision to orchestrate the end of gold convertibility under the guise of a monetary crisis? Were there shadowy and powerful private banking interests influencing events behind the scenes? And did the US close the gold window because they had far less gold than they claimed to have?

A 19 March 1973 US State Department cable, marked secret, refers to a 16 March 1973 meeting in Bonn between then US Secretary of the Treasury George Shultz and then West German Chancellor Willy Brandt, in which Shultz says that:

“huge deficits in the US balance of payments had occurred and had drained our gold reserves.

The week before August 15, 1971, a rush on those reserves forced the closing of our gold window bringing the end of convertibility.”

Very Interestingly, the word ‘drained’ is specifically used. ‘Drained’ is defined as ‘to deplete gradually, especially to the point of exhaustion‘, or ‘to become empty by the drawing off of‘. So, did the US Treasury even have half the gold it claimed to have in August 1971 or was Fort Knox already empty, and was this another reason for the sudden gold window closure?

These, however, are questions for another day.

One final point to note is that while the temporary suspension of the US Treasury gold window has been on-going for 50 years now and is a source of ridicule for the US Government due to the wording ‘temporary’, the last laugh is on the foreign central banks, since under international law, all of their billions of US dollar holdings prior to the 15 August 1971 gold window closure are still valid and legal claims against US Treasury gold holdings. Think about that for a moment.

Last Word to Arthur Burns

For now, the last word goes to Arthur Burns. the then chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System during August 1971, who wrote in his Green Notebook journal on 12 August 1971 that:

“My efforts to prevent closing of the gold window – working through Connally, Volcker, and Schultz – do not seem to have succeeded.

The gold window may have to be closed tomorrow [13 August] because we now have a government that seems incapable, not only of constructive leadership, but of any action at all. What a tragedy for mankind!”

Popular Blog Posts by Ronan Manly

How Many Silver Bars Are in the LBMA's London Vaults?

How Many Silver Bars Are in the LBMA's London Vaults?

ECB Gold Stored in 5 Locations, Won't Disclose Gold Bar List

ECB Gold Stored in 5 Locations, Won't Disclose Gold Bar List

German Government Escalates War On Gold

German Government Escalates War On Gold

Polish Central Bank Airlifts 8,000 Gold Bars From London

Polish Central Bank Airlifts 8,000 Gold Bars From London

Quantum Leap as ABN AMRO Questions Gold Price Discovery

Quantum Leap as ABN AMRO Questions Gold Price Discovery

How Militaries Use Gold Coins as Emergency Money

How Militaries Use Gold Coins as Emergency Money

JP Morgan's Nowak Charged With Rigging Precious Metals

JP Morgan's Nowak Charged With Rigging Precious Metals

Hungary Announces 10-Fold Jump in Gold Reserves

Hungary Announces 10-Fold Jump in Gold Reserves

Planned in Advance by Central Banks: a 2020 System Reset

Planned in Advance by Central Banks: a 2020 System Reset

Gold at All Time Highs amid Physical Gold Shortages

Gold at All Time Highs amid Physical Gold Shortages

Ronan Manly

Ronan Manly 0 Comments

0 Comments