Brazil Refuses to Answer Questions About Gold Reserves

This year has been shaping up to be a strong one for central bank gold buying. This is despite the official absence from the buy side of central bank gold powerhouses such as Russia and China.

Instead, there has been a noticeable trend of a diverse group of central banks who are not regular gold buyers, deciding to step up and make substantial gold purchases over short periods of time.

Thailand, Hungary and Brazil

First up in Europe was the central bank of Hungary, Magyar Nemzeti Bank (MNB), which stunned the gold market in early April, when it announced that it had bought 63 tonnes of monetary gold during March 2021. (See BullionStar article “Hungarian central bank boosts its gold reserves by 3000% in less than 3 years”).

Next up in Asia was the central bank of Thailand, Bank of Thailand, which revealed that over the two months of April and May 2021, it had added a total of 90 tonnes of gold to its reserves, specifically 43.5 tonnes during April, and another 46.5 tonnes in May ( See BullionStar article “Thai central bank leads pack, buying 90 tonnes of gold over April and May”).

And now most recently, the attention has moved to South America, where IMF data submitted by Brazil’s central bank, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB), reveals that after adding 11.7 tonnes of gold in May, the Brazilian central bank bought another 41.7 tonnes of gold in June, making a 2-month buying total of 53.5 tonnes of monetary gold. This now boosts Brazil’s gold reserves to a claimed 121 tonnes and puts South America’s largest economy in 32nd position in the sovereign monetary gold holding rankings.

After adding 11.7 tonnes of gold in May, the Brazilian central bank has now bought another 41.7 tonnes of gold in June, making a 2-month total addition of 53.5 tonnes of gold. Brazil now holds 121 tonnes of gold, putting it 32nd in global country gold rankings #Brasil #ouro #BCB pic.twitter.com/mHOgctTVYP

— BullionStar (@BullionStar) July 15, 2021

These three sets of gold buying from Thailand, Hungary and Brazil now make this trio the top 3 central bank gold buyers so far in 2021.

In the case of Thailand, 2021 was the first time since 2011 that the Bank of Thailand had made a substantial purchase of gold. In the case of Hungary, the 2021 purchase was only the second time it had entered the market for many years (the other time being Hungary’s large gold purchase of 28.4 tonnes in October 2018).

In the case of Brazil, 2021 was the first time since 2012 that the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) had gone out and purchased gold, and at 53.5 tonnes, was BCB’s largest gold purchase since the year 2000.

Brazil’s Gold Reserves – No Transparency

And then it suddenly struck me. No one seems to know very much at all about Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves. Look on the main pages of the BCB website about Brazil’s gold reserves, and you will find nothing. For a top 3 purchaser of gold during year-to-date 2021, this seems very odd.

For example, where are these gold reserves held and stored, and in what form? More importantly, where did the Banco Central do Brasil buy the gold that it claims to have bought so recently during May and June, and who was the seller?

What were the BCB’s gold buying motivations in adding 53.5 tonnes? And critically, does Brazil lend out its gold and only hold ‘claims on gold’, or does it hold only allocated and unencumbered gold bars in set-aside accounts with foreign central banks?

So I decided to put my questions to the BCB directly, whose headwuarters are in Brazil’s federal capital in Brasilia. And this is where it gets interesting. For while Hungary’s central bank was very forthcoming in explaining why it purchased 63 tonnes of gold during March (and even published a press release and photos of the gold bars purchased), the same cannot be said of the Banco Central do Brasil.

In my email to the BCB, I informed them that I was from BullionStar and that I was researching Banco Central do Brasil’s (BCB) gold reserves. My questions focused on why and where the recent claimed gold purchases of the Brazilian central bank were made, and in general where the Brazilian gold reserves are stored.

The email I sent to the BCB on 22 July was as follows:

“Hello,

I have some questions about BCB recent purchases of gold as part of the BCB’s international reserves policy.

According to IMF data, BCB purchased 11.7 tonnes of gold during May, and 41.7 tonnes of gold in June, making a 2-month total addition of 53.5 tonnes of gold, or about a 79% increase, and BCB now holds about 121 tonnes of gold.

Could you confirm:

• Why BCB boosted its gold reserves during May and June and how this relates to BCB’s international reserve policy, e.g. is gold being added for diversification purposes, or as a store of value, or as financial insurance etc

• The gold which BCB purchased during May and June (i.e. 53.5 tonnes), where was this purchased e.g. at the Bank of England in London or the BIS? And was this gold repatriated to Brazil?

• Where in general is the BCB gold stored, is it stored abroad, or is it stored domestically in Brazil?

• The gold which was purchased in May and June, is it in the form of allocated London Good Delivery gold bars or is it just gold ounces (pool allocated etc)?

• Does the BCB engage in gold lending with counterparties and if so, how much of BCB’s gold reserves are currently on loan?

• Does BCB ever buy domestically produced gold (i.e. from gold mining output in Brazil)?

-

Blanket Refusal – Top Secret

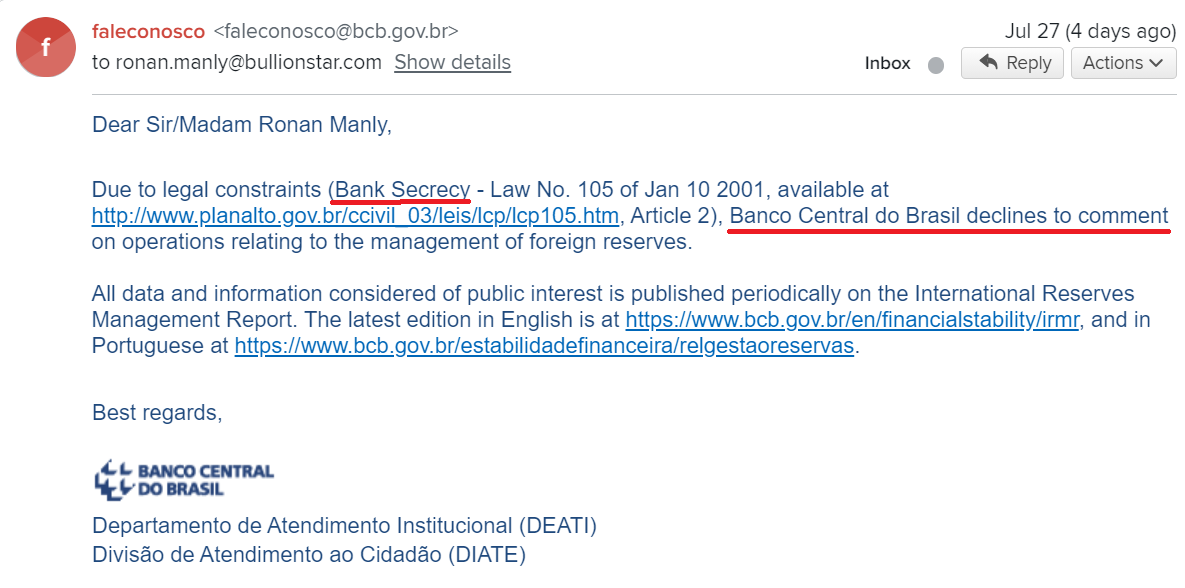

A few days later, the Brazilian central bank responded as follows:

“Due to legal constraints (Bank Secrecy – Law No. 105 of Jan 10 2001, available at http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lcp/lcp105.htm, Article 2), Banco Central do Brasil declines to comment on operations relating to the management of foreign reserves.

All data and information considered of public interest is published periodically on the International Reserves Management Report. The latest edition in English is at https://www.bcb.gov.br/en/financialstability/irmr, and in Portuguese at https://www.bcb.gov.br/estabilidadefinanceira/relgestaoreservas.

Best regards,

Departamento de Atendimento Institucional (DEATI), Divisão de Atendimento ao Cidadão (DIATE)”

While the BCB did respond, it outrageously refused to answer any of the questions I had posed, while immediately resorting to citing a domestic Bank Secrecy law from 2001 that provides blanket secrecy to it’s activities and operations.

Response from Brazil’s central bank on 27 July 2021, refusing to answer any questions about Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves. The BCB therefore refused to answer where it purchased the 53.5 tonnes of gold bought during May and June, in which form this gold was purchased, and where this newly purchased gold is now stored. And this is supposedly the 3rd largest sovereign gold purchase of 2021.

The BCB also refused to confirm where it’s existing gold reserves are stored (ie. the gold already claimed to be held before the new 53.5 tonnes additional claim), and furthermore the BCB refused to confirm whether it lends out it’s gold to bullion banks, i.e. whether it engages in gold lending.

The Brazilian central bank even refused to answer whether the BCB buys domestically produced gold that is mined in Brazil (which is a totally logical question given that Brazil is in the top 15 gold producing countries in the world).

The BCB response also had the audacity to state that “information that is considered in the public interest is published periodically”. You will notice that by saying this, the BCB is explicitly saying that it thinks that nothing about Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves is in the public interest.

The BCB response also linked to a completely irrelevant report in Portuguese on Brazil’s international reserves dated March 2021 (which was before the recent claimed BCB gold purchases had even been made). That report is useless in that it reveals nothing about Brazil’s gold reserves. The response also provided a similar link to an English version of the same report, but the version in English was even more outdated as it was published in October 2019. Again, revealing nothing about Brazil’s gold reserves.

In short, the BCB, like many central banks across the world, is arrogant and contemptuous of anyone asking about central bank gold reserves, while stonewalling genuine queries using blanket ‘bank secrecy’ laws.

Which begs the question, why the secrecy? Presumably Brazilian citizens in particular and anyone else for that matter, would generally agree that knowing about the location and composition of Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves is in the public interest.

Similarly, they would agree that the gold operations of the BCB and the management of Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves are also subjects that are in the public interest.

For if a 53.5 tonnes gold purchase has claimed to have taken place but no one can confirm anything about it, did it actually happen? Organisations like the IMF and the cheerleading World Gold Council will say yes it did happen, but neither outfit provides any proof.

LameStream Media

On 20 July, Brazil’s largest media group, Globo, wrote a story about the BCB’s 53.5 tonnes monetary gold purchase, but unfortunately the Globo reporters did not ask the BCB any questions while writing their article, nor does it seem to have dawned on the ‘journalists’ to do so.

Instead, the Globo reporters felt content to comment that:

“In its most recent report on the management of international reserves, published in March [2021], the BCB says very little about gold, merely commenting that according to law 4.595, of December 31, 1964, it is the sole responsibility of the Brazilian central bank to be depositary of official gold reserves."

Globo, which at this rate will never win any awards for investigative reporting in the gold market, then thinks it adequate to cite a kids’ brochure about the Brazilian central bank, and wait for it, a kid’s brochure that the BCB published 19 years ago:

“In Brazil, a BCB educational brochure, published in 2002, states that ‘a part of the reserves is kept in the vaults of the Central Bank, in the form of gold bars or bullion and in foreign coins and banknotes, protected by modern security systems’. ‘The BCB deposits another part of the reserve, the most important, in banks abroad,’ the document added.’”

Children’s brochure about the BCB published in 2002. One of Globo’s main sources Since Globo couldn’t be bothered to find out anything about Brazil’s sovereign gold reserves, I decided to do so (using my best Portuguese), and here is what I found.

Destroying the BCB’s Silence

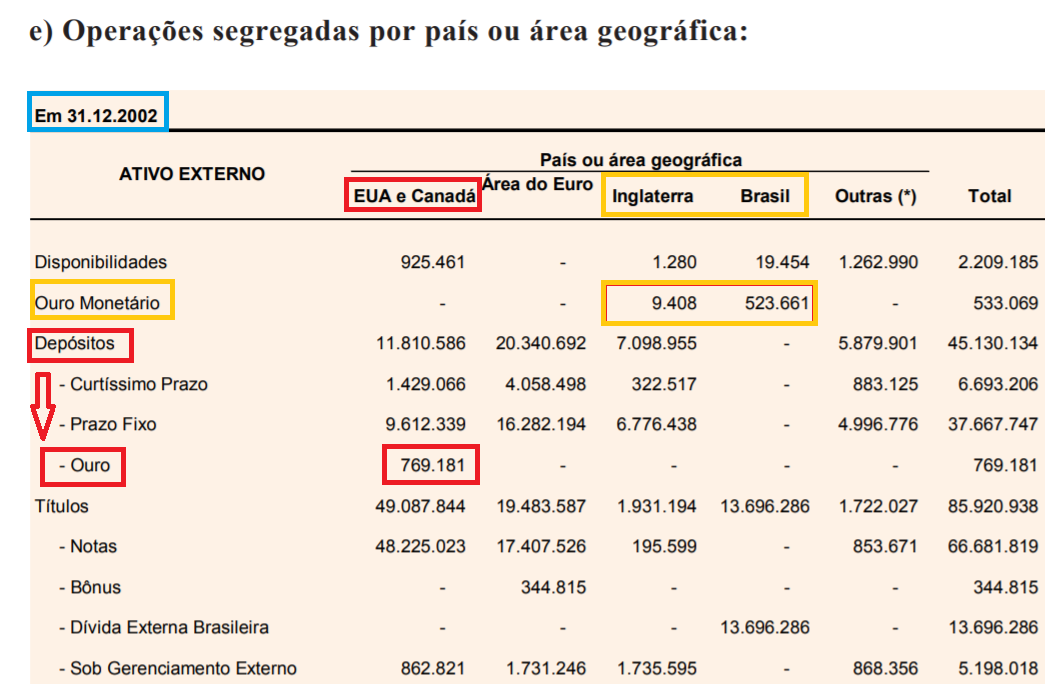

If we go back to the 2002 BCB Annual Report, we see that the BCB was more transparent about its gold goldings than it is in 2021. Here, the BCB said that it considered gold an active reserve and was engaged in gold operations “operações com ouro”.

In the 2002 annual report, there are ample references within tables of the Appendices to the fact that the Brazilian central bank held both monetary gold (Ouro Monetário) and 1-3 month ‘gold deposits’, both of which were classified as ‘external assets’ (Ativo Externo). The allocation was 41% monetary gold and 59% gold deposits.

These gold deposits refer to gold that central banks lend to LBMA bullion banks and which the central banks roll over continually with the LBMA bullion banks on a 1-3 month maturity basis, receiving interest on the loan. These gold deposits can remain outstanding for years on end, and the original gold lent by the central banks is long gone. Back then in 2002, when the BCB referred to ‘monetary gold’, it was probably referring to physically held gold to distinguish it from lent gold (which is a gold receivable).

Another table from the 2002 annual report shows that while the BCB classified ‘monetary gold’ with a high quality (low risk) Aaa risk classification, it classified it’s ‘gold deposits’ in a range from Aa1 down to Aa3. This is because (as yet another table in that report shows) the counterparties of the gold deposits were financial institutions (Instituições Financeiras), i.e. commercial banks. The counterparts of the monetary gold were listed as Supernational Institutions (Instituições Supranacionais), i.e. central banks.

Geographical distribution of Brazilian central bank gold in 2002. Source. An even more revealing table, titled “Operations segregated by country or geographic area” shows that less than 2% of Brazil’s monetary gold was held in England, with more than 98% held in Brazil. The monetary gold that was held in England with a Supernational Institution would presumably be the Bank of England.

Of the ‘gold deposits’, 100% of these were classified as being in “USA and Canada” (EUA e Canadá). Therefore the gold deposits were placed with US and/or Canadian entities of LBMA bullion banks. For example, Canadian or US branches of banks such as Scotia Mocatta and JP Morgan would fit this profile.

Fast forward to the 2010 edition of BCB Central Bank Management Report (Relatório de Gestão do Banco Central), and in a section referring to a project to improve the management of international reserves, the BCB states that one of the tasks completed was:

“opening a current account in GBP, associated with the custody of gold with the Bank of England”

(In Portuguese – “abertura de conta-corrente em GBP, associada à custódia de ouro, junto ao Bank of England” Page 57 of pdf

This reference is therefore 100% proof that during 2010, the Brazilian central bank held gold in custody storage with the Bank of England.

So based on 2002 and 2010 reports, we know that the BCB held monetary gold that was both stored domestically in Brazil and stored abroad at the Bank of England. The BCB also engaged in gold loans with bullion banks, resulting in ‘gold deposits’ (i.e. claims on those bullion banks), the gold deposits being gold liabilities for the unlucky bullion banks that got stuck holding the rolling short-term gold deposits).

Fast Forward again much more recently to 2018, and a BCB report titled ‘Financial Statements’ (Demonstrações Financeiras) 31 December 2018, states that part of the variation in the market value of the BCB’s gold holdings over 2018 referred to the ‘incorporation of gold’ into the reserves resulting from:

“the execution of location and quality swap operations of gold bars with the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) in order to adapt the country’s gold stock to international standards.

Through these operations, gold bars in the domestic standard and gold not standardized (Note 15) were sent to the BIS for processing and subsequent shipment of the standardized gold bars for custody in the Bank of England (BoE).”

Bingo! Yet more evidence that the Brazilian central bank holds gold at the Bank of England in London. The use of location swaps involving the BIS also shows that gold connected with the BIS was involved in the transactions, while the quality swaps (which are also called fineness swaps) show that some of the BCB’s gold holdings were of lower purity than 99.5%, hence the need to upgrade the ‘domestic standard’ to a London Good Delivery Standard.

This implies that domestically held Brazilian gold was probably shipped to Swiss refineries for melting / smelting, in the same manner that the Deutsche Bundesbank upgraded the low purity gold that it managed to extract out of the New York Fed (US Assay Office gold bars and coin bars) back in 2013 and 2014.

In the case of the Brazilian re-smelted Brazilian bars in 2018, these bars were then shipped to the Bank of England in London.

Turning to note 15 which is referenced above, this note says that:

“the location and quality swap operations of gold bars with the BIS … resulted in the write-off of non-standardized gold from the precious metals balance and the corresponding incorporation to the balance of monetary gold”.

This gold bar upgrading via location and quality swaps involving the BIS and the subsequent shipment of thee BCB gold to the Bank of England is mentioned in the BCB Financial Statements for 2018 but not similar reports for 2017 or 2019, suggesting that all the gold bar upgrading took place only in 2018.

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro (right) with Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) president Roberto Campos Neto (left). Conclusion

Establishment gold organisations such as the World Gold Council (WGC) will trumpet the news that central banks such as Brazil bought over 41 tonnes of gold during June but will not investigate beyond the headline, or alternatively, because of self-censorship, the WGC does not want to explain the real facts of how and where Brazil purchases it’s gold, as it involves a subject banned in the gold establishment – i.e. Central Bank Gold Operations and Gold Transactions.

The Brazilian central bank itself is totally unhelpful in providing any information on its claimed purchase of 51.5 tonnes of gold over May and June, the supposed third largest gold purchase by a central bank so far this year. The BCB resorts to Secrecy Laws and is totally untransparent, and even goes so far as arrogantly saying that information about the Brazilian sovereign gold reserves is not in the public interest.

The financial media (including the Brazilian financial media) don’t seem to think it’s important to investigate this issue nor do they ever ask questions to central banks about their gold reserves, and for example, Brazil’s giant Globo media and news organisation just resorts to referencing a kid’s brochure about the Brazilian central bank that was published nearly 20 years ago.

However, a few quick searches from myself blows all of this out of the water and destroys the BCB’s secrecy, shows up the financial media’s laziness, and highlights the World Gold Council’s fear to address the subject of central bank gold transactions and gold lending operations.

In fact, with a little bit of investigation, I have answered to some extent the questions that were put to the BCB and which they refused to answer.

Beyond the Globo reporters and their colleagues at the FT, Bloomberg and Reuters etc, there must be enquiring minds in Brasilia and Sao Paulo and across the world who will want to know the real facts about Brazil’s sovereign gold.

But where are the investigative reporters from the Brazilian and international media and news organizations? Why is the Brazilian central bank censoring this information? What does Brazil’s straight talking President Bolsonaro think of this BCB censorship and Globo’s lack of proper coverage?

Why, as GATA’s Chris Powell often says, are the “amounts, location, and disposition of government gold reserves are secrets more sensitive than the amounts, location, and disposition of nuclear weapons”?

Could it be that central banks know that monetary gold is a much more valuable asset than they would have you believe?

Popular Blog Posts by Ronan Manly

How Many Silver Bars Are in the LBMA's London Vaults?

How Many Silver Bars Are in the LBMA's London Vaults?

ECB Gold Stored in 5 Locations, Won't Disclose Gold Bar List

ECB Gold Stored in 5 Locations, Won't Disclose Gold Bar List

German Government Escalates War On Gold

German Government Escalates War On Gold

Polish Central Bank Airlifts 8,000 Gold Bars From London

Polish Central Bank Airlifts 8,000 Gold Bars From London

Quantum Leap as ABN AMRO Questions Gold Price Discovery

Quantum Leap as ABN AMRO Questions Gold Price Discovery

How Militaries Use Gold Coins as Emergency Money

How Militaries Use Gold Coins as Emergency Money

JP Morgan's Nowak Charged With Rigging Precious Metals

JP Morgan's Nowak Charged With Rigging Precious Metals

Hungary Announces 10-Fold Jump in Gold Reserves

Hungary Announces 10-Fold Jump in Gold Reserves

Planned in Advance by Central Banks: a 2020 System Reset

Planned in Advance by Central Banks: a 2020 System Reset

Gold at All Time Highs amid Physical Gold Shortages

Gold at All Time Highs amid Physical Gold Shortages

Ronan Manly

Ronan Manly 0 Comments

0 Comments