Why SGE Withdrawals Equal Chinese Gold Demand and Why Not

This post is part of the Chinese Gold Market Essentials series. Click here to go to an overview of all Chinese Gold Market Essentials for a comprehensive understanding of the largest physical gold market globally. This post was updated in 2017.

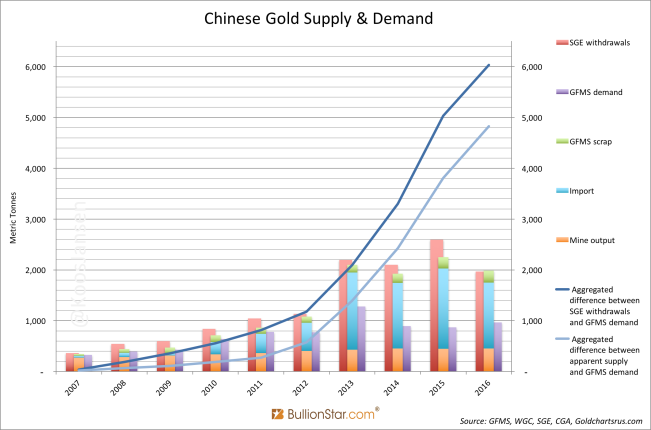

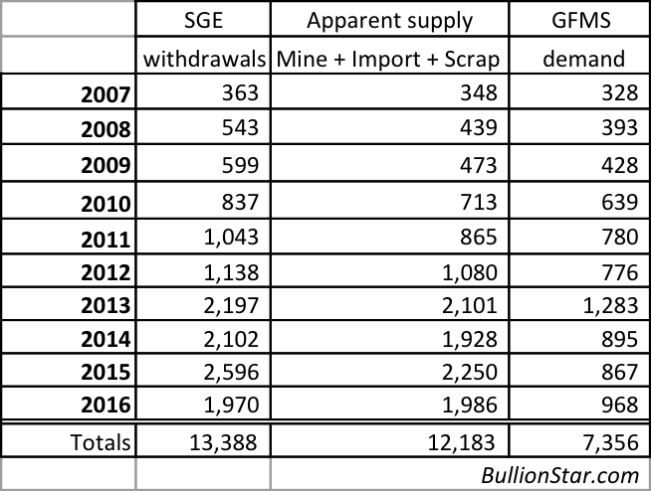

The difference between SGE withdrawals and Chinese consumer gold demand as disclosed by GFMS has aggregated to a staggering 6,032 tonnes from 2007 until 2016 (the period this article will focus on). To explain the difference, GFMS and other Western consultancy firms have presented several arguments in publications and lectures at conferences throughout the years, though none of them can really explain the difference in full. This post is an overview of all such arguments – supplemented by my own arguments.

The reason I tend to compare SGE withdrawals to Chinese gold demand as disclosed by GFMS, and not Metals Focus or CPM Group, is because the GFMS is globally the easiest (free) accessible data source for investors (next to the World Gold Council). Usually investors and news agencies worldwide consult GFMS (or WGC) for supply and demand statistics, which make this the most important firm to test for accurate numbers. Below we’ll examine to what degree the arguments can or cannot have caused the difference.

This is the argument list (by GFMS, WGC and CPM Group) in chronological order:

- Industrial demand (August 2013)

- Stock movement change (August 2013)

- Round tripping (April 2014)

- Leasing (April 2014)

- Official purchases (April 2014)

- Recycled distortion (November 2014, February 2015, March 2016)

- Export (May 2015)

- Chinese commercial banks’ balance sheets

- Financial statement window dressing (March 2016)

- Retailers selling unsold inventories directly to refiners (March 2016)

These are my arguments:

- The Shanghai International Gold Exchange

- Smuggling

In 2014 the World Gold Council (WGC) came out with two special reports about the Chinese gold market that for the first time ‘should have’ shine a light on the difference (China’s Gold Market: Progress And Prospects from April 2014, and Understanding China’s Gold Market from August 2014). However, these reports contained many false statements and the segments on the difference failed miserably. As I’ve pointed out in several posts (one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight).

Surprisingly, after the reports were published and I had debunked the arguments in it, the WGC and GFMS swiftly came up with brand new arguments. Note this shift in arguments; when the old ones failed, the firms impudently moved on and came up with new ones. The fact the argument list is constantly changing confirms the weakness of all arguments it holds, and the apparent ‘ignorance’ of Western consultancy firms regarding the Chinese gold market. (By the way, eventually in late 2016 I found out why Western consultancy firms lie about Chinese gold demand, which is explained in my post The Great Physical Gold Supply & Demand Illusion.)

First, let’s go through all the arguments to investigate which ones make any sense. At the end of the post we’ll do some number crunching.

1) INDUSTRIAL DEMAND. The first argument ever presented to me came from the WGC. In August 2013 I’ve asked the Council what their explanation was for the difference between their Chinese gold demand numbers and demand as disclosed in the CGA Gold Yearbooks co-written by the PBOC – the latter exactly equals SGE withdrawals. They replied to me by email:

The data that we publish in Gold Demand Trends are collected for us by Thomson Reuters GFMS. Our data represent jewelry and bar & coin demand and do not incorporate any industrial demand or fabrication, which is included in the PBoC figures. As I am sure you will appreciate, data collection of this sort relies on a number of proprietary sources and these will not necessarily be the same for both GFMS and PBOC. It is, therefore, perhaps not surprising that the estimates of demand differ somewhat.

The WGC identified a gap of, at that point, 2,000 tonnes of gold with industrial demand. Not very credible. Additionally, in Q1 2015 the WGC started including industrial demand (technology) in its data, and as far as I know GFMS has always included industrial demand in its data. So, for our comparison of SGE withdrawals versus GFMS demand this argument is irrelevant.

2) STOCK MOVEMENT CHANGE. When I asked GFMS in August 2013 about net investment – which is how the difference was titled in the CGA Gold Yearbooks – they wrote me by email:

We have checked with our Data Specialist and confirmed that we use a different methodology. Total Chinese demand used by Thomson Reuters GFMS only includes jewelry, physical bullion bars/coins and all industrial demand. Any stock movement change (which is essentially the item 6 net investment) will not be included as underlying demand.

Me:

So according to you category six is “stock movement change”? This would be gold added to the stocks from jewelers, the mint, industrial companies, etc? (this is a few hundred tons each year!)

GFMS:

That’s correct based on the resolution provided by our data specialist.

Because SGE withdrawals capture wholesale demand the difference is partially what jewelry companies, refineries, industrial companies and the mint have purchased at the SGE, but not yet sold in retail. And so, stock movement change is a legitimate argument, though the amount of gold in stock can never explain the full difference of 6,032 tonnes.

According to an estimate by the WGC as much as 125 tonnes of gold can have been absorbed as inventory in the Chinese domestic gold market from 2009 until 2013:

… It is, however, indicative that as jewelers expanded, so too did their inventory levels and it is our judgment that across the industry between 75t to 125t may have been absorbed in the supply chain since 2009.

Stock movement change is a legitimate argument and its volume, 125 tonnes, will be taken into account for our calculation of true Chinese gold demand at the end of this post. I will stick to the number 125 because in my opinion the jewelry and coin industry in China hasn’t grown since 2013 (meaning inventory stayed flat).

3) ROUND TRIPPING. In April 2014 the WGC published a report titled China’s Gold Market: Progress and Prospects. It certainly was not the first WGC report on China – in 2010 China Gold Report was released – but it was the first time the Council elaborated on the structure of the Chinese gold market, the Shanghai Gold Exchange and the “supply surplus" in the Chinese gold market. Logically, the Council had some explaining to do, as it was clear China imported substantially more gold than what they disclosed as demand.

For the first time Chinese Commodity Financing Deals (CCFD) were introduced to the Council’s wide reader base. This type of financing is pursued to acquire cheap funds. It can be done trough round tripping or gold leasing. The Council wrote:

These operations fall into two broad categories, although there is some overlap between the two. Firstly, there is the use of gold via loans and through letters of credit (LCs) as a form of financing. Secondly, there is the use of gold for financial arbitrage operations that will also be based upon gold loans or LCs. In most cases the gold is quickly re-exported to Hong Kong, often as very crude jewellery or ornaments to get round tight controls on bullion exports. (This is the practise commonly referred to as ‘round-tripping’. Moreover, because nearly all gold flowing into China goes through the SGE, round-tripping can inflate the SGE delivery figures.) In other cases the metal is stockpiled in vaults in China or Hong Kong.

In particular the part in bold is not true, as we could read in my previous posts Chinese Cross-Border Gold Trade Rules and The Chinese Gold Lease Market And Chinese Commodity Financing Deals Explained. Basically, round tripping gold flows are completely separated from the Chinese domestic gold market and the SGE system, therefor they can not inflate SGE withdrawals.

So round tripping is not a legitimate argument. To my understanding the WGC has abandoned this argument all together, though GFMS still thinks round tripping inflates SGE withdrawals. In their Gold Survey 2015 it’s written (page 78):

…the round tripping flows between Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, which also inflates the SGE turnover and withdrawal figures…

4) GOLD LEASING. The other CCFD is leasing. In the WGC report from April 2014 it’s stated:

No statistics are available on the outstanding amount of gold tied up in financial operations linked to shadow banking but Precious Metals Insights [PMI] believes it is feasible that by the end of 2013 this could have reached a cumulative 1,000t…

PMI insinuated 1,000 tonnes is tied up in CCFDs, but as I’ve clearly demonstrated in The Chinese Gold Lease Market And Chinese Commodity Financing Deals Explained, this is not true. There is no need to go over this again – if you wish please read my previous post for a detailed analysis. (Even the WGC has turned its back on this argument.)

5) OFFICIAL PURCHASES. Often it’s being thought in the gold space SGE withdrawals end up in the vaults from the People’s Bank Of China (PBOC). Early 2014 the WGC (in China’s Gold Market: Progress And Prospects) speculated the difference could be explained by official purchases, though, later that year the Council changed its mind. From the July 2014 WGC report on China, Understanding China’s Gold Market, we can read:

China’s authorities have a range of options when purchasing gold. They may acquire some of the gold which flows into China; there has been no shortage of that. But there are reasons why they may prefer to buy gold on international markets: gold sold on the SGE is priced in yuan and prospective buyers – for example, the PBoC with large multi-currency reserves – may rather use US dollars than purchasing domestically-priced gold. The international market would have a lot more liquidity too.

In my post PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation I’ve analyzed why the PBOC does not purchase gold through the SGE. The firms (WGC and GFMS) must agree with me by now and thus official purchases cannot make up the difference we’re after.

6) RECYCLED DISTORTION. The most obvious argument to explain elevated SGE withdrawals, one would think, is recycled gold through the bourse counted over and over as withdrawn. However, SGE rules state bars withdrawn are not permitted to re-enter the vaults before being remelted and assayed by an SGE approved refinery. Which is not say it doesn’t happen.

Arguments presented by the firms regarding recycled gold must be divided in subcategories. There is process scrap, arbitrage refining, and there are VAT schemes.

6.1) Process scrap. This argument was first presented by CPM Group. In short, CPM states industrial companies produce 50 – 70 % scrap supply of the gold used in manufacturing. The scrap spillover flows directly back to the SGE. Process scrap thus inflates SGE demand and supply, because the gold was bought at the SGE (demand), but a significant part flows back to the SGE (supply). The part that is recycled through the SGE has no impact on the price.

Although, it’s unknown how much of process scrap actually flows back to the SGE or is brought to a refinery for toll refining (a refinery producing bars or wire from the process scrap for the industrial company in return for a fee).

Process scrap, described first in detail by Jeffrey Christian in November 2014 in the chapter “CPM Group" at the very end of this post, is a form of recycled distortion, and is a legitimate argument.

6.2) Arbitrage refining. This argument was brought forward by GFMS on 17 February 2015 at the Reuters Global Gold Forum when Jan Harvey interviewed Samson Li (GFMS).

Jan Harvey:

Some people see withdrawals on the Shanghai Gold Exchange as a proxy for Chinese demand. Do you think this is valid?

Samson Li:

It depends on the methodology used. For example there are refiners that would, at times, withdraw 9995 gold bars from the SGE, refine it into 9999 bars whenever there is profitable opportunity, and then deposit it back into SGE vault……

Presumably, there can be an arbitrage opportunity at the SGE if Au99.95 gold is an X percentage cheaper than Au99.99 gold. Such a spread would be a classic example of one of the contracts being under or overvalued relative to the other.

I’m not a trader, but I can imagine a way to close the arbitrage through gold leasing. This is my theory: if a spread occurs Au99.95 is bought, concurrently Au99.99 (LAu99.99) is borrowed and immediately sold. Then the Au99.95 is withdrawn, refined into Au99.99 and returned to the lender.

If the arbitrage described above exists, inter alia depends on the speed to which a lease contract can be settled. If a spread occurs and the refiner has to wait 2 days before it can take delivery of Au9999, the arbitrage won’t fly. I’ve asked the ICBC gold lease desk what would be the fastest possibility to sign a lease contract. They told me usually it takes several days or weeks as the lessee’s credit rating must be determined. Though, for regular customers the lease ca be executed in one hour.

It’s hard for me to say if arbitrage refining is really possible according to the aforementioned theory, because it depends on many variables and the established relationship between lessor and lessee. In addition, why would anybody sell Au99.95 if it was undervalued? In my opinion the argument that arbitrage refining inflates SGE withdrawals can be doubted.

6.3) VAT schemes. This argument brought forward by GFMS in The Gold Survey 2016 is legitimate. Though, it’s unknown to what extent it has been used. Read more about the value-added tax system in China’s domestic gold market by clicking here, and read why I think the VAT scheme can only have had a limited impact on SGE withdrawals in the chapter “Tax Avoidance" in this post.

7) EXPORT. This argument was brought forward by PMI. On a conference in London (2 May 2015) Phillip Klapwijk, Managing Director of Precious Metals Insights Limited (PMI), stated China exports about 1,000 tonnes a year from the domestic gold market. However, at this stage the rules prohibit gold export from the Chinese domestic gold market. I’ve written an extensive analysis on Klapwijk’s presentation (click to read), no need to go over this again here. The export argument is not legitimate.

8) CHINESE COMMERCIAL BANK BALANCE SHEETS. Over the years, on countless gold blogs the “precious metals" (more than 2,500 tonnes by now) on Chinese commercial banks’ balance sheets have been identified as the “surplus" in the Chinese gold market. But not according to my research. After a thorough study I think the gold on the banks’ balance sheets reflect a mixture of GAP gold, retail inventory, gold held for hedging, gold outside China, but most importantly back-to-back leasing and synthetic leasing. The leasing business by banks can make it appear the banks “own" gold assets, while in fact it’s just accounting that makes it seem that way.

For a full analysis read my post What Are These Huge Tonnages In “Precious Metals” On Chinese Commercial Bank Balance Sheets?. The commercial bank balance sheets are not a legitimate argument in my very humble opinion.

9) FINANCIAL STATEMENT WINDOW DRESSING. Another argument that was presented by GFMS in their Gold Survey 2016. In short, the argument is false. If you want to know why please read the chapter “Financial Statement Window Dressing" in this post.

10) RETAILER SELLING UNSOLD INVENTORIES DIRECTLY TO REFINERS. Another argument that was presented by GFMS in their Gold Survey 2016. The argument can be true. If you want to learn more please read the chapter “Retailers Selling Unsold Inventories Directly to Refiners" in this post.

11) THE SHANGHAI INTERNATIONAL GOLD EXCHANGE. This argument was conceived by myself. As we could have read in The Workings Of The Shanghai International Gold Exchange (and SGE Withdrawals In Perspective), the gold withdrawn from the SGEI vaults in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone (SFTZ) – note, this tonnage is included in “SGE withdrawals" – can, (i) either be imported into the Chinese domestic gold market, or, (ii) exported abroad and thereby distorting Chinese wholesale gold demand when measured by SGE withdrawals. However, up until December 2015 we know SGEI withdrawals have rarely been exported abroad, according to several sources.

Another way of checking possible SGEI withdrawals that have been exported abroad is simply examining the gold imports of all countries on earth from China since 2014. As far as I can see the exports from China have been tepid. For example, 7 tonnes were exported to Thailand in 2015 and 8 tonnes to the UK in 2016, but that’s about it. Except for Chinese exports to Hong Kong: in 2016 these accounted for roughly 90 tonnes. But, most likely this gold didn’t come from the SFTZ (SGEI), but from the Shenzhen Free Trade Zone just across the border from Hong Kong where China’s jewelry manufacturing base is located. Gold export from the Shenzhen Free Trade Zone to Hong Kong has existed long before the SGEI was erected (and these flows are offset when I compute net gold flows into China from Hong Kong). How it works is that Shenzhen gold manufacturers import gold through processing trade, fabricate the materials into jewelry and ornaments after which the finished products are exported through processing trade back to Hong Kong where they are sold locally or distributed across Asia.

All in all, I’m still not seeing a lot of gold being withdrawn from SGEI vaults and exported abroad.

One last possibility that would inflate “SGE withdrawals" is when (Asian) central banks buy gold on the SGEI, after which it’s withdrawn and exported. Because central banks can monetise gold, which is exempt from being disclosed in customs data, we would never see these exports out of the SFTZ. Effectively we would only see export to China and high SGE withdrawals, while gold is withdrawn in the SFTZ and covertly exported abroad. At this point not a very plausible scenario because SGEI gold trades at a premium from gold in London, Singapore, Hong Kong, etc, but certainly possible.

12) SMUGGLING. Naturally, smuggling can cause SGE withdrawals to be inflated. Indians could buy gold in Shenzhen, withdraw from the SGE vault and smuggle it home. Although, we have no numbers on smuggling so I can’t take it into account for our calculation of true Chinese gold demand.

How Much Is True Chinese gold Demand?

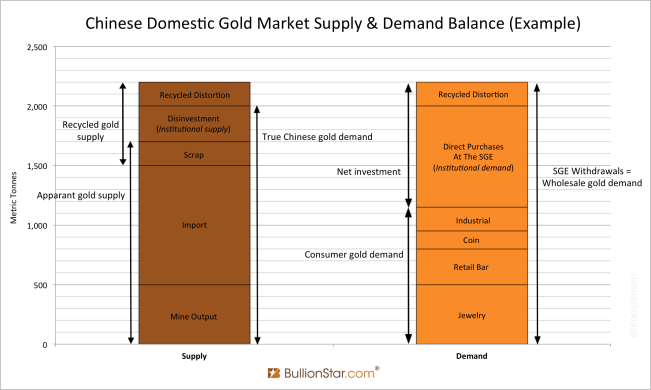

The answer is we don’t know. But we can set a lower and upper bound. Remember the equations and the graph from The Mechanics Of The Chinese Domestic Gold Market.

True Chinese Gold Demand = Import + Mine + Scrap + Disinvestment = SGE Withdrawals – Recycled Distortion

Unfortunately we don’t know how much disinvestment is in China, and as a consequence neither do we know recycled distortion. But we’ll set the lower bound by apparent supply and upper bound by SGE withdrawals, and work from there.

From 2007 until 2016 apparent supply in the Chinese domestic gold market – assuming all net exports from the UK, Switzerland, Australia and Hong Kong went to the domestic market and SGEI vault inventory is insignificant – was 12,183 tonnes, and total SGE withdrawals over this period accounted for 13,388 tonnes.

So the lower bound of true Chinese gold demand over 2007-2016 was 12,183 tonnes, and the upper bound was 13,388 tonnes. Adjusting the upper bound by wholesale inventory increase (125 tonnes) makes 13,263 tonnes. Effectively, true Chinese gold demand must have been somewhere in between 12,183 tonnes and 13,263 tonnes (instead of the 7,356 tonnes GFMS has presented the world). Let’s, for the sake of simplicity, take the middle of the 12,183 and 13,263 as a number for true Chinese gold demand to work with – which is 12,723 tonnes.

The gap between GFMS demand (7,356 tonnes) and our estimate of true demand (12,723 tonnes) is a staggering 5,367 tonnes. It’s impossible to deny this immense tonnage has not been demand from high net worth individuals and institutions, purchased directly at the SGE. Although, the remaining difference between 12,723 tonnes and 13,263 tonnes could have been caused by process scrap, VAT schemes, retailers selling unsold inventory to refiners etc.

Ironically, the WGC wrote in its recent GDT Q2 2017:

Purchases made directly from the SGE continued to gain traction accounting for a significant proportion of Q2 bar demand. Investors benefit from better pricing bars from the SGE are usually 5-10 yuan per gram lower than those bought from commercial banks – and a sense of security from knowing they are buying gold from a trusted provider. With a minimum lot size of 100 gram direct withdrawals from the SGE largely serve China’s high net worth individuals.

Finally, after four years of debating (between me and the WGC/GFMS) the WGC admits that the majority of the difference simply reflects direct purchases of high net worth individuals and institutions at the SGE. Case closed.

To this date, October 2017, I still think SGE withdrawals provide a useful indicator of Chinese wholesale gold demand.

Popular Blog Posts by Koos Jansen

China’s Secret Gold Supplier is Singapore

China’s Secret Gold Supplier is Singapore

Audits of U.S. Monetary Gold Severely Lack Credibility

Audits of U.S. Monetary Gold Severely Lack Credibility

China Gold Import Jan-Sep 797t. Who’s Supplying?

China Gold Import Jan-Sep 797t. Who’s Supplying?

The Gold-Backed-Oil-Yuan Futures Contract Myth

The Gold-Backed-Oil-Yuan Futures Contract Myth

Estimated Chinese Gold Reserves Surpass 20,000t

Estimated Chinese Gold Reserves Surpass 20,000t

Did the Dutch Central Bank Lie About Its Gold Bar List?

Did the Dutch Central Bank Lie About Its Gold Bar List?

PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation

PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation

U.S. Mint Releases New Fort Knox Audit Documentation

U.S. Mint Releases New Fort Knox Audit Documentation

China Net Imported 1,300t of Gold in 2016

China Net Imported 1,300t of Gold in 2016

Why SGE Withdrawals Equal Chinese Gold Demand and Why Not

Why SGE Withdrawals Equal Chinese Gold Demand and Why Not

Koos Jansen

Koos Jansen