SGE Withdrawals At Record High 1,958 Tons YTD

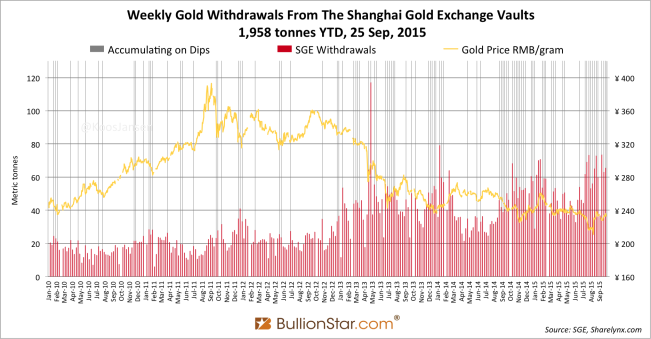

Year to date withdrawals from the vaults of the Shanghai Gold Exchange (SGE) came in at a staggering 1,958 tonnes on 25 September 2015 – a record high – according to data released by the SGE on Friday. In week 38, which runs from 21 September until 25 September, 66 tonnes of gold were withdrawn from the vaults. The weak price of gold throughout 2015 and the crashing Chinese stock market has stimulated the Chinese people to purchase gold in great quantities.

As I’ve been away from reporting on SGE withdrawals for a while, I’ll try to catch up in this post (which has been preceded by my post from 12 October about Chinese gold import in the first six months of 2015) on trading activity at the SGE and several other topics in the Chinese gold market. We’ll run through it!

It’s advised you’ve read “The Mechanics Of The Chinese Domestic Gold Market” to have a basic understanding of the physical supply and demand flows through the Shanghai Gold Exchange. In short, SGE withdrawals equal Chinese wholesale demand.

In my previous post we’ve learned that in 2015 there is probably more recycled gold supply flowing through the SGE relative to what is withdrawn. In 2013 the mixture between recycled gold, imports and mine supply was 11 %, 69 % and 20 %. In 2014 and 2015 the share of recycled gold has grown, although definitive data has yet to be published, which lowers the share of gold import that supplies the SGE. Nevertheless, China is on track to import more than 1,300 tonnes of gold in 2015, making it by far the largest buyer ahead of India.

The next chart that runs from January 2013 until August 2015, displays the composition of known Chinese new gold supply (import + mine) plotted against SGE withdrawals.

Kindly note, Chinese gold import as shown in the chart above only reflects gold export data from Hong Kong, Switzerland, the UK and Australia. However, China also imports gold from other countries that are less transparent in publishing merchandise trade statistics.

The gaps between SGE withdrawals and the center columns can have been filled either by recycled gold or import. All easily accessible data from global customs departments combined points out China has imported at least 865 tonnes of gold year to date. The recycled gold that is supplied to the SGE can be:

- Gold-for-cash. This is a phrase coined by the World Gold Council, for the sake of simplicity I’ll stick with it. Gold-for-cash includes jewelry that is sold to refineries. It’s true supply because gold is exchanged for yuan, therefor it is captured by any metric as supply.

- Gold-for gold. This includes, for example, scrap spill over from jewelry or industrial fabricators. The scrap metal cannot be used for production and will be exchanged for new bars or wires. These transactions potentially find their way through the SGE (inflating SGE withdrawals). Because the supply part of gold-for-gold is offset by an equal amount of demand it has no net effect on the supply-demand balance and is therefor by most metrics not captured as true supply.

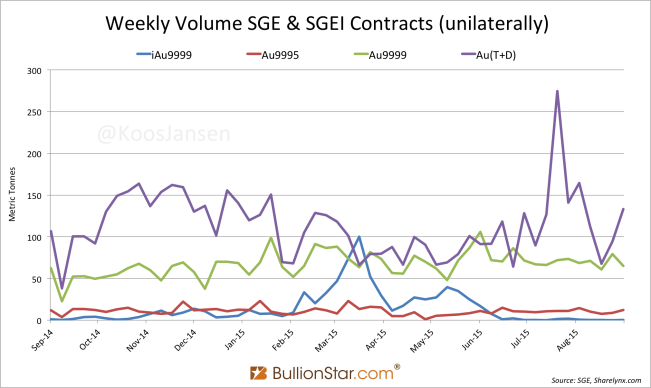

Trading volume on the Shanghai International Gold Exchange (SGEI) has been declining in recent months. Meaning, it’s not likely there is much physical gold flowing through the international bourse in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone. If gold is withdrawn from vaults in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone this would be captured in SGE withdrawals, potentially blurring our view on wholesale demand in the mainland. Because SGEI volume has been tiny, I assume it has had little impact on SGE withdrawals so far. In the chart below the blue line represents the contract iAu9999 that is traded on the SGEI, the other contracts we can see in the chart are traded on the SGE. After a peak in March SGEI volume has fallen to almost zero.

Let’s have a look at the weekly SGE withdrawals chart.

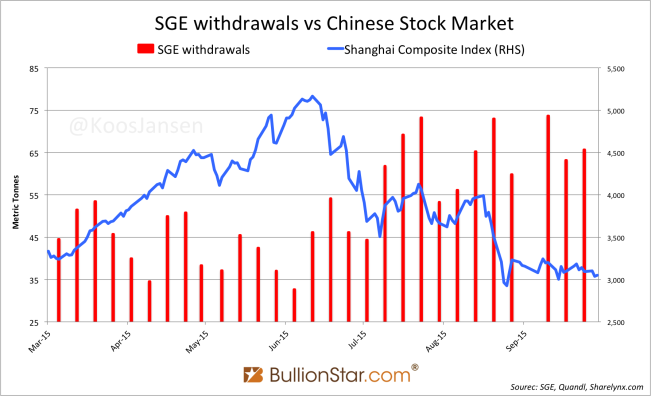

What I notice is that SGE withdrawals continue to be inversely correlated to the price of gold; the lower the price of gold, the higher SGE withdrawals. Though, the devaluation of the renminbi on 11 August 2015 has not stopped the Chinese from buying. Another boost for SGE withdrawals has been the crash of the Chinese stock market. The Shanghai Composite Index (SCI) peaked on 11 June 2015, when SGE withdrawals were seasonally low. But from that moment on SGE withdrawals have made an exceptional run up and the SCI a huge downfall, from 5,000 points to 3,000.

In July, August and September SGE withdrawals have shown exceptional strength. Premiums have kept up over this period – reflecting pressure on imports.

In addition, since the devaluation of the renminbi (mid august) the gold price has rallied and the US stock market has declined. We will follow these trends.

Sharps Pixley came out with an article this week (referring to a Bloomberg study) about the large discrepancy between SGE withdrawals and Chinese gold demand as disclosed by the World Gold Council (WGC). The argument presented is that Chinese Commodity Financing Deals (CCFDs) are inflating SGE withdrawals, which can only be true to a certain extent in my opinion. What is described in the article, to my understanding, is round tripping that is done between Hong Kong and Free Trade Zones in China mainland. These gold flows are separated from the Chinese domestic gold market, where imported gold is required to be sold through the SGE, as I’ve written in my post “Chinese Gold Trade Rules And Financing Deals Explained”. Round tripping does not inflate SGE withdrawals and therefor cannot cause the discrepancy between SGE withdrawals and WGC demand. Other CCFDs include gold leasing at the SGE. Technically, this can inflate SGE withdrawals though speculators that lease gold to acquire cheap funds are more likely to sell it spot at the SGE, in order to use the proceeds, instead of withdrawing the metal. For them the metal is not important, they just want to borrow gold at a low interest rate to promptly sell it for yuan. This way a cheap loan is acquired.

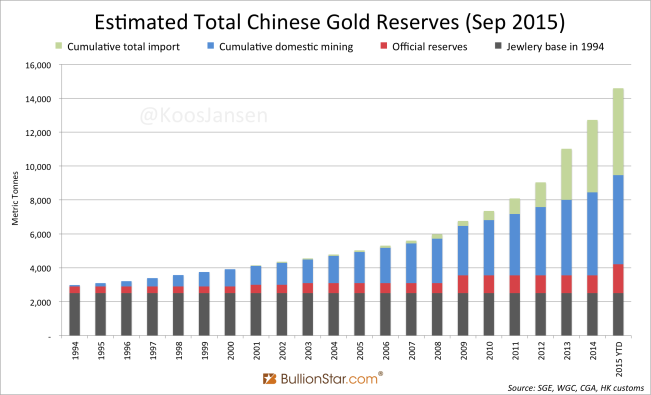

Friday we learned the People’s Bank Of China (PBOC) has increased its official gold reserves in September, this by time by a modest 14.9 tonnes, while its foreign exchange reserves declined by $43.3 billion to $3.514 trillion. Total PBOC official gold reserves are now at 1,708.5 tonnes. According to my analysis there are now approximately 14,593 tonnes of gold in China mainland (if the PBOC has bought all its monetary gold abroad since 2007).

On Thursday the PBOC published a press release on its website that states the weight of the new Panda bullion coins will no longer be denominated in troy ounces but in a grams. The global standard for bullion coins is troy ounces, the Chinese are now going solo by changing their base weight. Internationally gold is quoted in US dollars per troy ounce, while the Chinese price gold in yuan per gram. The decision to mint the new Panda’s in grams can be seen as Chinese gold policy is becoming more independent, breaking away from the US dominated sphere.

H/t @BullionBaron

The new Panda coins will be launched 28 October 2015. Gold Panda coins will be available in 1 gram, 3 gram, 8 gram, 15 gram, 30 gram, 50 gram, 100 gram, 150 gram and 1 kilogram, and silver Panda coins in 30 gram, 150 gram and 1 kilogram.

Popular Blog Posts by Koos Jansen

China’s Secret Gold Supplier is Singapore

China’s Secret Gold Supplier is Singapore

Audits of U.S. Monetary Gold Severely Lack Credibility

Audits of U.S. Monetary Gold Severely Lack Credibility

China Gold Import Jan-Sep 797t. Who’s Supplying?

China Gold Import Jan-Sep 797t. Who’s Supplying?

The Gold-Backed-Oil-Yuan Futures Contract Myth

The Gold-Backed-Oil-Yuan Futures Contract Myth

Estimated Chinese Gold Reserves Surpass 20,000t

Estimated Chinese Gold Reserves Surpass 20,000t

Did the Dutch Central Bank Lie About Its Gold Bar List?

Did the Dutch Central Bank Lie About Its Gold Bar List?

PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation

PBOC Gold Purchases: Separating Facts from Speculation

U.S. Mint Releases New Fort Knox Audit Documentation

U.S. Mint Releases New Fort Knox Audit Documentation

China Net Imported 1,300t of Gold in 2016

China Net Imported 1,300t of Gold in 2016

Why SGE Withdrawals Equal Chinese Gold Demand and Why Not

Why SGE Withdrawals Equal Chinese Gold Demand and Why Not

Koos Jansen

Koos Jansen